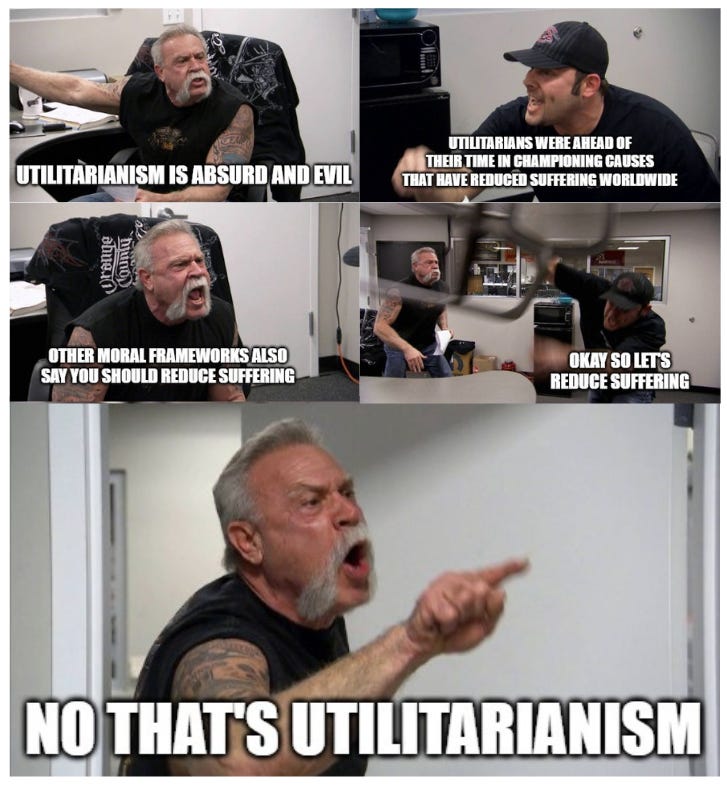

Consequentialism is a scary word. It’s an “-ism” that is closely associated with utilitarianism, which is another scary “-ism” and, for many, a dirty word. One way to object to anyone’s ethical claim or argument is to simply declare that it assumes a version of consequentialism, immediately a reductio ad absurdum. On the contrary, consequentialism is not as scary as people think, once people figure out what the view actually says.

In this article, I will explain what consequentialism is, but mostly what it isn’t, and respond to some bad objections to it along the way. Unlike what most people seem to think, not everything is utilitarianism.

Consequentialism vs Utilitarianism

Let’s start by distinguishing the two “-isms” mentioned in my (sub)title, as consequentialism and utilitarianism are related but are not the same thing. Consequentialism is a moral theory that says we should do our moral best, and we do our moral best by maximizing moral value. Utilitarianism is a particular kind of consequentialism that says only one thing has (intrinsic) moral value: wellbeing. Wellbeing (welfare) is what is good for something (usually persons and animals).1 So, utilitarianism says we should maximize wellbeing, and that principle exhausts our (fundamental) moral obligations. Non-utilitarian consequentialists, on the other hand, are open to more than just wellbeing having intrinsic moral value (as we will see).

Thus, consequentialism is a broad class of moral theories, of which utilitarian theories are a subset. So, utilitarianism may be false while some other version of consequentialism is true, but if all versions of consequentialism are false, then utilitarianism is false. Much of the point of this article will not hinge on distinguishing the two, but I point out a few cases where the difference matters.

In summary, consequentialism says: maximize moral value (of all kinds), while utilitarianism says: maximize wellbeing (as it’s the only thing with moral value).

What Consequentialism is NOT

Some people are pretty confused about what consequentialism is. Examples include this guy and this person and this guy and basically everyone who commented on this article and many of Effective Altruism’s critics and many more. If you have found yourself thinking, “This argument implicitly assumes some form of consequentialism”, especially as a response to someone saying “we should prevent really bad things from happening”, chances are you found yourself in the trap of totally misunderstanding consequentialism. Read the rest of this article to find out if that may be true.

I will start with pointing out a few things consequentialism is NOT to make sure we are on the same page.

What Isn’t Consequentialism

Some people get really scared when they see certain features in a discussion about ethics, cry “consequentialism!”, and declare victory. It is common for these cries of “consequentialism!” to be deeply confused, such as everything that happened recently in the shrimp welfare discourse. Here are some things that are not the same thing as, nor do they imply, consequentialism:

Using numbers or rankings in moral reasoning

The concept of outweighing goods

Thinking some outcomes are better than others (and this is morally relevant)

Using thought experiments to derive moral implications

It is okay to hurt someone to help or save a sufficiently large number of people

A good person (or God) would tend to try to prevent bad things from happening

Violating some deontic constraints is sometimes permissible

Many view some subset of this list of ten as 1) inherent in consequentialism and 2) objectionable on moral grounds. In reality, both of these are incorrect. None of these principles picks out consequentialism from any other plausible ethical theory, and all of these principles are obviously true (though it’s certainly not my goal in this article to defend these truths). Since I find objections to these principles so incredibly uninteresting, I will instead hope my detailing of what consequentialism actually is can be more helpful in seeing how principles 1-10 differ from and do not entail consequentialism (and thus are either irrelevant or not uniquely relevant for evaluating consequentialism as a moral theory). Much of what is actually contentious in arguments about utilitarianism is really a question of aggregation, which is an orthogonal moral debate to the consequentialism vs deontology vs virtue ethics debate.2

While I won’t individually defend these principles here, which would mostly consist of explaining why every plausible moral view endorses each of these things, I will at least refer to other discussions of a few of them. For example, I argue here that everyone already thinks ends sometimes justify the means, nobody thinks ends always justify the means, and neither of these statements have anything to do with consequentialism as a moral theory. Richard Chappell has a nice post on how refusing to quantify tradeoffs is basically just refusing to think about moral decisions that we simply have no choice but to make in our everyday life (though I’m no Fanatic). Ibrahim Dagher argues that even without assuming utilitarianism, suffering is bad, actually (radical!). Finally, I would like everyone to witness my favorite conversation about the Problem of Evil of all time, which I think truly settled the matter once and for all.

As you can see, since moral perfection doesn’t lead us to predict that a perfect agent would attempt to reduce suffering (it does), and the Problem of Evil assumes consequentialism (it doesn’t), we have successfully solved the Problem (okay I do think there are some good responses to the PoE, but I’m not defending that here).

The only other thing I’ll say is that the only plausible version of deontology, threshold deontology (also called moderate deontology), accepts in a very explicit way the idea that really good consequences (or the prevention of really bad consequences) can outweigh a bad action and justify violating a constraint if the consequences are significant enough; this alone takes care of maybe half the list above.

So, objections to pretty much all of the above list are confused attempts to avoid serious moral thinking, not legitimate ways to characterize or object to consequentialism.

What Isn’t Anti-Consequentialism

On the other hand, there are ideas that some people think are inconsistent with consequentialism (and thus provide a reductio of consequentialism) that are not. The following is a list of things that are compatible with consequentialism that people mistakenly think otherwise:

Intentions matter morally

One’s motivations matter intrinsically, not just instrumentally

Killing is always wrong

Genuine moral dilemmas

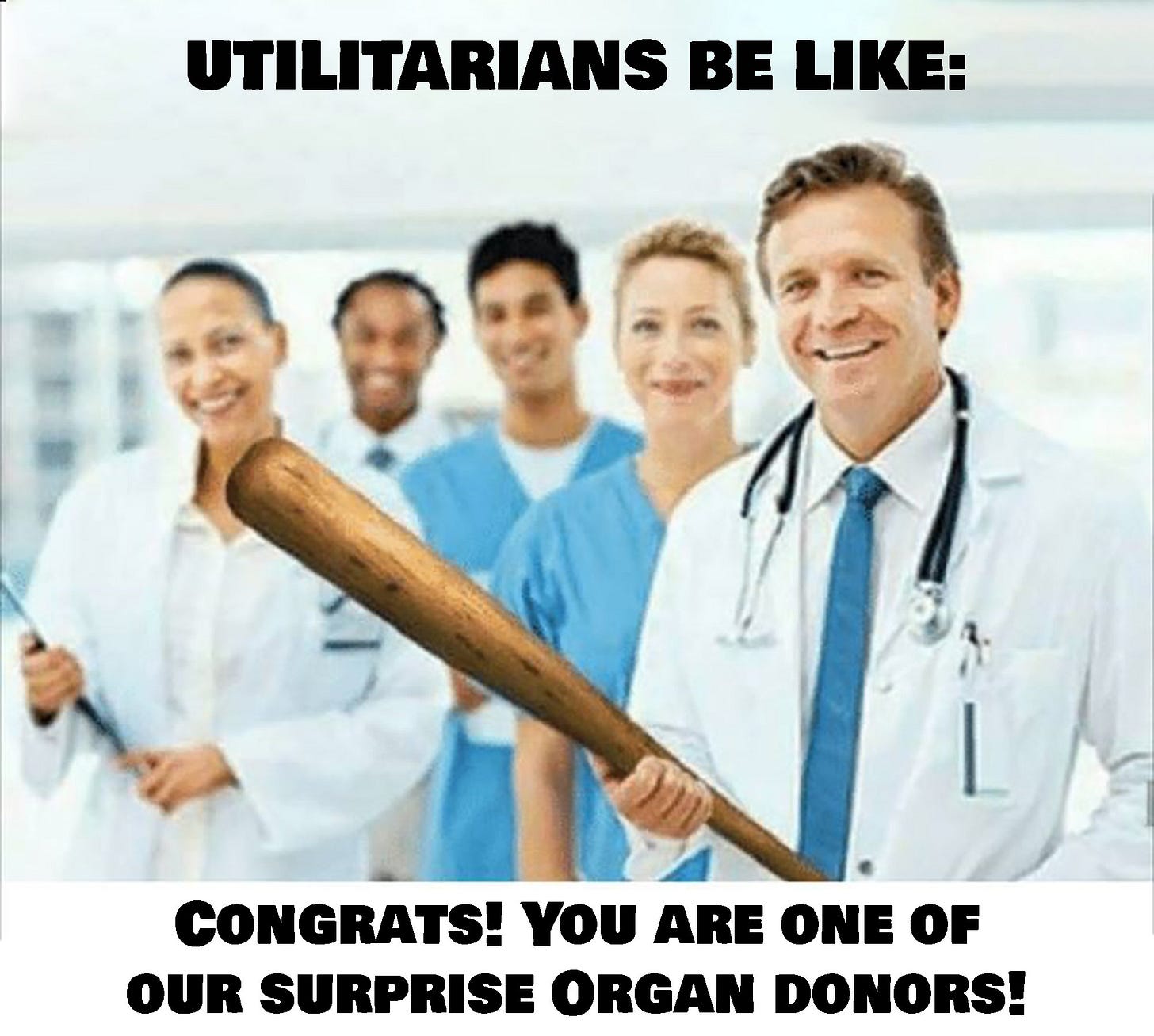

It’s wrong to kill the innocent to save more people (e.g., surprise organ donation)

You shouldn’t be doing moral calculus to think through your decisions

Ought implies can

We should not punish the innocent to appease an angry mob

We have special obligations to family and loved ones

We should prioritize those worse-off more than those well-off

Each of these items is, in fact, compatible with at least some version(s) of consequentialism, even if they may be incompatible with other versions of it. I will briefly summarize how a consequentialist theory can adopt each of these principles into their moral theory, though there may be more than one way to do this:

Choose actions based on how they contribute to forming the best intentions, which are themselves ranked based on their likelihood or tendency to produce the best outcomes (Robert Adams’ motive consequentialism)

Simply count motivations as intrinsically valuable, and maximize good motivations + whatever else one counts as intrinsically valuable

Assign infinite disvalue to killing (with temporal discounting of future killings so you make sure it is impermissible to kill even to prevent more future killings)3

See this paper, which requires very complicated buffoonery (such as using hyperreal numbers) to make it work, which I think shows how silly it is to accept genuine moral dilemmas in the first place

Count killing as very bad, much worse than how good saving a life is

Combine a consequentialist criterion of rightness with a distinct decision-making procedure that does not include moral calculus (such as a virtue-based procedure)

When evaluating the best action, only compare actions that one has the ability to perform

Count punishing the innocent as very bad, or consider second order effects

Include love as intrinsically valuable (perhaps scaled with strength of love), or give family members’ welfare a higher moral weighting

Give the worse-off greater moral weighting, such as in prioritarianism or sufficientarianism (Wikipedia, SEP)

There is a common theme in how to account for these supposed objections to consequentialism: simply choose certain kinds of things to have (dis)value of certain levels/degrees. Just make it happen. You can assign whatever things you want to have levels of (dis)value of whatever you want.4 Obviously, you’re still under the same epistemic constraints as any other moral reasoner, and the view will only be as plausible as your value assignments and resulting deontic outcomes (aka whether actions are permissible, obligatory, impermissible, etc.). Given that guideline, the world is your oyster.

How to Know Things are Valuable

There are two primary thought experiments I have seen proposed to determine if something has (intrinsic) value. I will just consider the first, which is the isolation test, proposed by G.E. Moore.5 The isolation test assesses the value of an object by “considering what value we should attach to it, if it existed in absolute isolation, stripped of all its usual accompaniments.”6 Using this isolation test, I think we can reasonably conclude that various things mentioned in the lists above have corresponding intrinsic value or disvalue, such as one’s intentions, love, persons, and friendship. I can know some things are intrinsically valuable because I can think about them and (internally) observe their value; I contemplate some states of affairs and ascertain that some states are desirable, and some are more desirable than others.7

These value assignments may (also) be done in order to meet certain pretheoretical conditions, such as it being wrong to punish the innocent, with the goal of ending in a reflective equilibrium between one’s theoretical and pretheoretical intuitions. The English translation of the previous sentence is: the goal of moral inquiry is a happy medium between intuitions about general moral principles and intuitions about specific cases, progressively modifying the general principles to account for various particular thought experiments. An example of a pretheoretical intuition is that it is wrong to let an innocent person be punished to satisfy a lynch mob.

This general approach to moral epistemology is called reflective equilibrium, a phrase coined by John Rawls, and is probably the most widely used method in moral reasoning. There are interesting objections to, and variations of, this method, but I won’t reply to those here. Some have given arguments for consequentialism based primarily on theoretical intuitions, defending the evidential superiority of theoretical over pretheoretical intuitions, such as Bentham’s Bulldog and Richard Chappell, and Peter Singer attempts an evolutionary debunking argument against the reliability of our pretheoretical intuitions.8

One might respond to this procedure of selective value assignment by saying that even if it is possible for a consequentialist moral theory to have these features, real-world consequentialist theories don’t have these features, so these objections stand. I’m sympathetic to a version of this response. For example, utilitarianism, the most popular subset of consequentialism, limits what one can assign intrinsic value to, so only welfare (wellbeing) has intrinsic value. Thus, utilitarians cannot say intentions matter intrinsically, only that some intentions lead to more welfare than others and thus are more instrumentally valuable.9

I don’t mind happily agreeing with the anti-consequentialist here and rejecting utilitarianism for that basis (among others). But there are a large number of consequentialisms on offer that do not restrict themselves to welfare maximization. In fact, consequentialism is really a family of an infinite number of theories, rather than a single theory (ditto for deontology and, presumably, virtue ethics).10 In addition, even utilitarians can account for many of these objections by appealing to second-order effects, e.g. a society where you can’t trust your doctor to help you rather than harvest your organs would be much worse. Alternatively, they can adopt a rule utilitarianism that endorses actions in accordance with certain rules, where the adoption of such rules (e.g., never kill) leads to the best consequences.

There will very likely be no objection that can wipe out all versions of consequentialism in a single blow, though one may erase a significant fraction of otherwise plausible consequentialisms.11 I think the versions of consequentialism paraded by the mast famous consequentialists, particularly hedonistic utilitarians like Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, and (later) Peter Singer, are less interesting than what I find to be the most plausible versions of consequentialism. We should attempt to construct the best version of our opponent’s view before taking them down, so ruling out consequentialism as a whole in virtue of demonstrating an inconsistency with a fraction of consequentialisms is not a promising procedure. One should find the most plausible versions of consequentialism, which I think will consider many things to have intrinsic value other than welfare, such as friendship, persons, knowledge, intentions, love, etc., and then look for objections to that view.

Conclusions

While this article was mostly explaining what consequentialism is NOT, my next article will give a more detailed account of what consequentialism IS. In the meantime, here is a quick cheat sheet of takeaways from today’s exploration.

Maximize moral value = Consequentialists

Maximize wellbeing = Utilitarians

Suffering is bad = Everyone with a conscience

Thought experiments can tell us about morality = Every ethicist

Ends sometimes justify means = Everyone

Quantifying trade-offs is worthwhile = Serious moral persons

Remember kids, not everything is utilitarianism.

There are multiple accounts of wellbeing in the literature. The most common three are hedonism, desire satisfactionism, and objective list theory. Hedonism says that wellbeing consists of pain and pleasure mental states, perhaps some of these “higher pleasures” are qualitatively better than other “lower pleasures”. Desire satisfactionism says that what matters for wellbeing is satisfying one’s desires and not frustrating one’s desires, perhaps suitably restricted to get rid of various kinds of defective desires. Objective list theory says that what is good for a person is an objective list of things, perhaps including items like friendship, knowledge, etc. constitutively (as opposed to instrumentally). I opt for the objective list theory, I find desire satisfactionism plausible if sufficiently restricted (but restricted enough that we might as well be objective list theorists at that point), and I think hedonism is basically a non-starter (sorry Bentham). So, even if we are sticking to evaluating utilitarianism and not consequentialism more generally, I think we should consider more sophisticated and plausible versions of utilitarianism that are not just the hedonistic versions.

Every plausible moral theory is “minimally aggregative”, by which I mean “we have a pro tanto reason to impartially promote value” (from Wilkinson, Hayden. "Infinite aggregation: Expanded addition." Philosophical Studies 178.6 (2021): 1917-1949). This reason can be overridden, but impartial value obviously gives a pro tanto reason to promote it.

See Schroeder, S. Andrew. "Consequentializing and its Consequences." Philosophical Studies 174.6 (2017): 1475-1497, p. 1479.

If you’re thinking, “But only consequences can have intrinsic value on consequentialism!”, see the section “What are Consequences?” of my next article (not published yet). Basically, anything can count as a consequence (intentions, lies, cheating, happiness, etc.). It’s worth mentioning that there is a debate about the proper “bearers of value” in normative ethics, whether it is objects, states of affairs, locations, times, or whatever. This debate is orthogonal to one’s axiology in the sense I’m talking about, as the value of “consequences” can be put in the form of value placed in each of those things, depending on whatever it turns out the proper value-bearers are.

I may elaborate on the use of these tests, as well as the other test, the annihilation test from Scott Davison, in a future post.

I wouldn’t say being valuable is identical to being desirable, but being valuable implies being desirable in such a way that desirability provides good evidence of value (probably). I suspect “value” or “valuable” is a primitive not analyzable in other terms, following Moore.

Singer, Peter. "Ethics and Intuitions." The Journal of Ethics 9.3 (2005): 331-352.

That is, unless one thinks intentions are constitutive of one’s wellbeing. But, surely, that is an implausible view. Even if it were plausible, the fact that one’s intentions are constitutive of wellbeing would probably be best explained as a special case of a more general principle that doing intrinsically morally good things is constitutively good for you, in which case it would have to be that intentions already have intrinsic value apart from wellbeing, and thus utilitarianism would still be false.

The question of how to individuate theories for distributing credences is extremely important and vexing (especially given infinite theories) for dealing with moral uncertainty, but that does not concern us here.

Although, if one has a very strong intuition that the fundamental explanatory relation is wrong, then that could settle the matter fairly quickly, at least for which family of theories is correct. But we still have a long way to go to get to a fully-fleshed out theory (with deontic predicates, etc.) even if that’s true.

I do think a lot of the items on your not-anti-consequentialism list can only be accommodated by, at minimum, agent relative consequentialism, and I prefer to define consequentialism by maximizing impartial/agent neutral value; but I’m aware this isn’t an agreed aspect of the definition :)

This is a helpful reminder, but I think the definition you provide of consequentialism is quite problematic.

“Maximize moral value = Consequentialists”

How does this render Consequentialism distinct from other ethical theories? Doesn’t *every* ethic try to maximize moral value?

Consider what most books position as the opposite of Consequentialism, the Kantian deontological ethic. Kant, too, is trying to maximize moral value. He just thinks one achieves that goal through performing rational duties.

So if we can’t distinguish Kant from Bentham using this definition, is it really the best definition of Consequentialism?