What the Heck IS Consequentialism?

An Exploration and Defense of the Best Moral Theory

Now that we’ve come to understand what consequentialism is not, we can get into the meat of a positive exposition of consequentialism. In this article, I will spell out how to distinguish between moral theories, fully characterize consequentialism, and provide an argument for maximizing consequentialism. Finally, I will clarify the notion of “consequences” to correct a common misconception and articulate which kind of consequences matter morally. By the end of this article, you will discover the correct moral theory and thus have all your moral questions fully settled (jk).

Consequentialism is a moral theory, alongside virtue ethics and deontology as the three most commonly named families of moral theories, which says that the rightness of an action is explained solely by the moral evaluation of the consequences of that action.

The Explanatory Criterion

Consequentialism can fundamentally be characterized as:

Fundamental Consequentialism: An action is right only because of the moral value of its consequences

This characterization highlights what makes consequentialism consequentialism: only consequences factor into the explanation of why actions are right or wrong. The “because of” phrase specifies that consequentialism aims to provide an explanatory relation between the consequences of an action and the rightness of that action. The consequences are what explain why an action is right. This explanatory relation is, surprisingly, what actually differentiates consequentialism from the other families of moral theories. It may turn out that versions of deontology or virtue ethics also say the right action (at least sometimes) has the morally best consequences, but what actually makes it right or explains why it is right, is not the consequences but its virtuousness or its (lack of) violations of deontic constraints.

It is not enough that a theory simply tells you THAT an action is wrong, but a moral theory needs to tell you WHY an action is wrong. Maybe an illustration will help. Imagine that you, Bob, get told your boss is unhappy. Perhaps he looks suspiciously like the image below.

Obviously, that’s no good. You can’t just leave it there, and he wouldn’t want you to leave it at that either. It’s not enough to know THAT your boss is unhappy, but you need to know WHY your boss is unhappy. So, you should probably ask him a question, like, “why?” But if he’s anything like Mr. Incredible’s boss, not any “why?” question will do. Be specific, Bob.

In the movie, the golden ticket question is, “Why are you unhappy?” The corresponding golden ticket question for moral theory is, “Why are actions right or wrong?” This question is the fundamental question that all moral theories must answer. The fundamental answer consequentialists will always give to “why was this action wrong?” is “because it made the world worse than it could have been (had you done otherwise)”. The fundamental answer to “why is this action right?” is “because it makes the world as good as you could make it” or (equivalently) “it results in the most moral good”.

The importance of the explanatory aspect of consequentialism is made clear when you see that any non-consequentialist theory can be turned into a consequentialist theory via “consequentializing”.1 When this is done, both the non-consequentialist theory and its consequentialist equivalent have identical deontic predicates (i.e., both theories say that all the same actions are either permissible or obligatory or whatever). In this case, then, the only difference between these theories would be what makes the action right or wrong (or, equivalently, what explains why the action is right or wrong) and not which actions are right or wrong. I will discuss this idea and its consequences more in a future post. The most important implication is that any objection to the consequentialist family of theories of the form “consequentialism says X is right, but X is actually wrong” fails immediately, as one can always construct a consequentialist theory that says X is wrong (or right), for any X.

The Conditions of Rightness

Thus far, however, we have not specified the conditions in which an action is right. Presumably, a moral theory would not say an action is right because its consequences were the worst conceivable consequences. So, the consequences need to good consequences, or the best consequences, or at least good enough.

The most general2 way of characterizing consequentialism that specifies the explanation of and conditions for rightness is given by General Consequentialism:

General Consequentialism: An action is right if and only if and because its consequences are sufficiently morally good

This characterization is still a little vague, but it highlights some points of significance. First, the “if and only if” part signifies that consequentialism specifies necessary and sufficient conditions for the rightness of actions. This designation is what makes consequentialism be giving a criterion of rightness, which are the necessary and sufficient conditions for when an action is right.

Second, as discussed earlier, the “because of” part specifies that consequentialism aims to provide an explanatory relation between the consequences of an action and the rightness of that action. Consequences explain why an action is right or wrong, and the moral value of consequences are what make an action right or wrong.

Both the conditions and explanation of rightness together specify and distinguish consequentialism. For the philosophy nerds, consequences are the “rightmakers” of actions (consequences are what makes actions right), analogous to “truthmakers” of propositions. In the same way that truthmaking is distinguished from and may be separate from the truth conditions of a proposition, rightmaking is distinguished from and may come apart from the “right conditions” of actions in different moral theories, which is why one needs the explanatory relation in addition to the “if and only if” statement to fully characterize consequentialism.

But, surely, “good enough” isn’t good enough. We don’t just want the consequences to be “good enough” to make an action right, as satisficing consequentialists say (those lazy bums, smh). We should always do the morally best thing, obviously! Clearly, it is wrong to intentionally do something worse than your best. Therefore, we need to make clear that “good enough” should actually be replaced with “the best”, bringing us to the best moral theory out there, the correct one.

The Best Moral Theory

The true moral theory has the following general specification:

Maximizing Consequentialism (MC): An action is right if and only if and because it has the morally best consequences.

In case you had any uncertainty about which moral theory is correct, let me relieve you of it: Maximizing Consequentialism is the best moral theory, hands down.

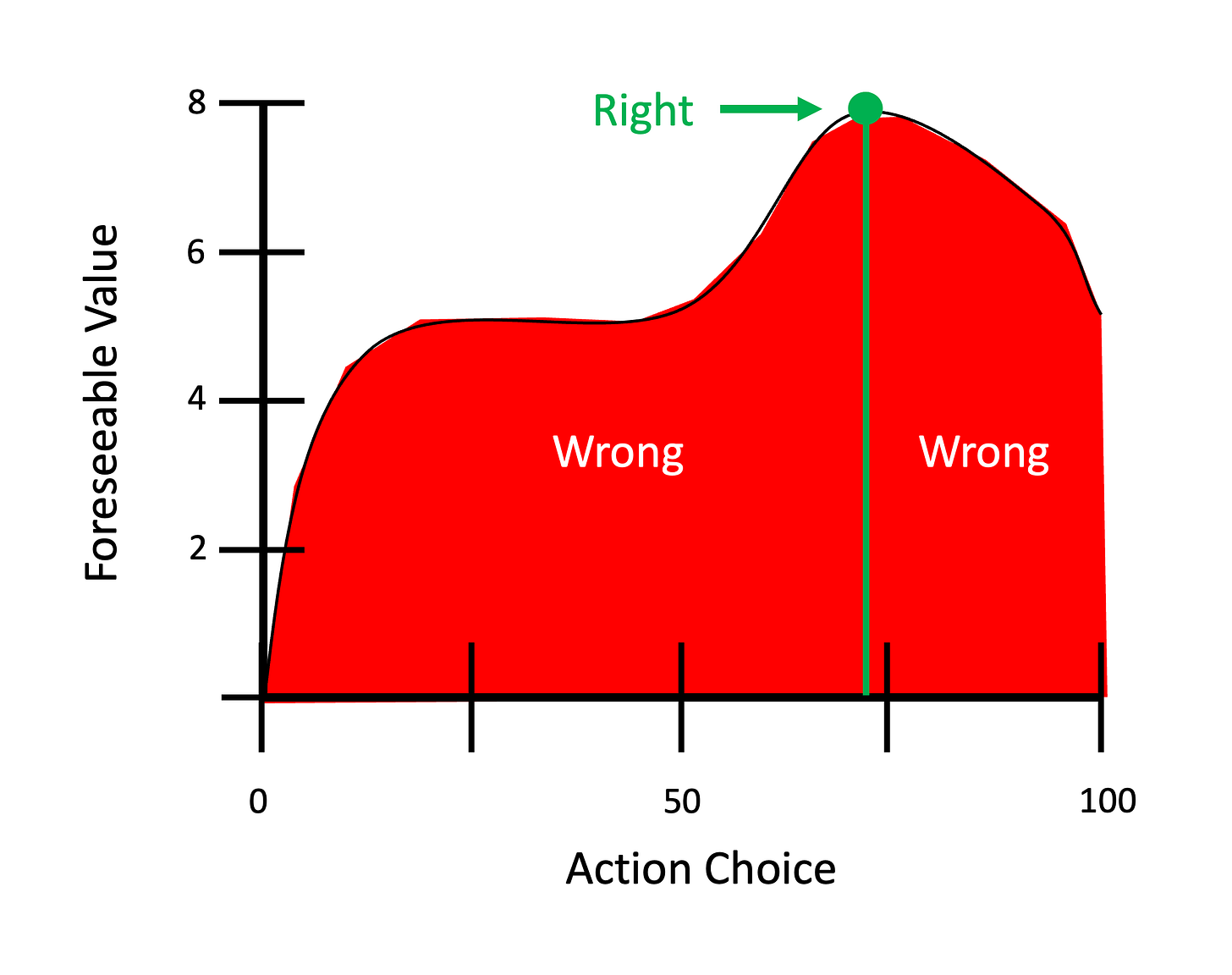

Like any good scientist, I like to have a visual representation of things where possible. So, look at this graph.3 Don’t take the quantitative aspects too seriously (or the shape of the curve, or the fact that it’s continuous or positive, etc.), but I just want to present the main idea. The idea is that you compare how much good will result from some action with any other possible action, and the right action is the one that is better than or at least as good as the rest, while all other actions are wrong because they are non-optimal. If you knowingly do worse than what you could do, that is morally wrong.

An Argument for Maximizing Consequentialism

I can’t fully defend Maximizing Consequentialism here, but one argument for MC is based on the Compelling Idea4 that it is permissible to bring about the best thing:

It is always permissible to bring about the most good.5

If (1) is true, then Maximizing Consequentialism is true.

Therefore, Maximizing Consequentialism is true.

Since my point in this post isn’t to defend consequentialism, I won’t exhaust this discussion, but there is some reason believe this argument. The first premise is hard to deny. Good luck with that (and good riddance). Regarding (2), consider what other theories say about consequences. Since consequences are not fundamental to other moral theories, it’s hard to see why there would be a necessary link between the morally best outcome and the right action. There may be a deontic constraint that makes it impermissible to bring about the most valuable outcome. Sometimes, morally best outcomes do not justify improper means, so it would be impermissible. But, surely, it really is at least permissible to bring about the most value to the world and make the world go best. It’d be like saying, “No, you’re actually not allowed to improve the world as much as you can, sorry.” Like, what?

Similarly, consider the implications of the consequentialist criterion of right action: an action is either impermissible or obligatory. There is no in between. Thus, if an action is permissible, then it is obligatory.6 So, it is obligatory to bring about the morally best outcome. Yet, this is exactly the Maximizing Consequentialists’ criterion of rightness. Thus, since MC entails the Compelling Idea aka premise (1) (and the Compelling Idea entails the MC criterion7), and other moral theories seem to not entail or appear to be inconsistent with it, then MC gets a big plausibility boost from this highly intuitive idea that it is permissible to bring about the best moral outcome.

In the MC criterion, the action with the “morally best consequences” is determined by comparing the consequences of each action with the consequences of all other possible actions. To evaluate which action is right, we consider the value of the world that results if I do action A, and compare it to the value of the world that results if I do action B, and again with action C, and so on, until I have compared every action in my option set, which is the set of actions (options) I can perform.8 When comparing the moral value of the world relative to each of the actions, the right action is that one that is at least as good (i.e., produces at least as much good) as all the other actions, and every other action is wrong. This type of analysis constitutes what is meant by “morally best consequences” in MC.

Note that this account does not specify how you should actively, consciously reason about making decisions (commonly called a decision-making procedure), nor does it specify what your motives should be. MC is entirely compatible with a moral theory that entails that you should never once consciously consider what action has the morally best consequences, if it turns out that never consciously considering the morally best consequences is expected to produce a better outcome. This clarification is discussed in “The Three Components of a Complete Moral Theory”.

Next, I want to clarify what things even count as consequences at all, as this question causes a lot of confusion in popular discussions about consequentialism. People tend to assume consequences = causal effects of an action and so think consequentialists are severely restricted in what things count as valuable, but this is not the case.

What Even Are “Consequences”?

Some people think it’s silly to only care about “consequences” as morally relevant, but this objection is usually based on a misunderstanding of what “consequences” even are in the context of consequentialism. In this context, consequences are not simply what follow from (i.e., the causal effects of) some action, unlike how the word is used in common parlance. What consequentialists care about is the overall value of the world and thus which actions will make the world overall better or worse.9 An action’s value, on its own (if it has any), obviously contributes to the overall value of the world. The effect of performing this action is, in part, in its own value contribution to the world. This observation is why G.E. Moore describes his consequentialism this way:

“In asserting that the action is the best thing to do, we assert that it together with its consequences presents a greater sum of intrinsic value than any possible alternative."

Further, any action can reasonably be described as a consequence of some prior action, so any action can be considered a morally relevant consequence. For example, having an intention is a consequence of forming an intention, telling a lie is a consequence of deciding to tell a lie (or of speaking a certain way), etc. Acts and consequences can be arbitrarily partitioned. Thus, there is no interesting act-consequence distinction.10

One straightforward way of understanding this non-distinction is that the first and foremost consequence of performing an action is that the action was performed. An action is its own consequence. By doing X, I brought it about that X, or I caused X to be done. A consequence of telling a lie is that a lie was told. One consequence of donating money to GiveWell is the exemplification of the virtue of generosity, which may be intrinsically valuable. Obviously, we do not need to restrict the badness of killing to solely the downstream effects of killing, i.e. only after the death of the other individual, but the killing itself is the (most) relevant consequence! As the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy puts it:

“Consequentialism holds that actions do matter, because they are among their own consequences.”

In sum, consequentialists care about the value of actions and whatever follows from them, and both of these, actions + causal effects, are considered consequences.11 If the moral value found inherent in that action in addition to its downstream effects is better than all alternative actions, then it is the right thing to do.

Which Consequences Matter?

Another important factor in versions of consequentialism is which consequences are considered morally relevant: is it the expected consequences (called subjective consequentialism) or is it the actual consequences (objective consequentialism)? Consequentialists differ on this, but I will give a brief argument for a variant of subjective consequentialism that depends on the foreseeable consequences, neither the foreseen (expected) nor the actual consequences.

Against Expected Consequentialism

We should not base our moral evaluations on merely what is actually expected or foreseen because there are obviously cases in which one is morally culpable for what one could have known, if they had gathered the right evidence (evidence they should have gathered, and thus they should have known) or should have known even given their current evidence. For example, Nikil Mukerji gives the following case,

Poisonous Medicine: Smith gives Jones a medicine which, unbeknownst to him, is poisonous and kills Jones. Smith expected that the medicine would cure Jones. However, given the evidence available to him, he should, in fact, have been able to foresee that it would kill the guy.12

In this case, Smith expected, or foresaw, that Jones would be cured, but in fact Jones was killed. Yet, Smith should have known better. We can imagine a case where the medication had a warning about certain allergic reactions in Smith’s documentation, and Jones’ medical file prominently mentioned an allergy to that exact medication. In this case, Smith clearly did something (morally) wrong. Smith was negligent. So, it is not the foreseen or expected consequences that matter, but these consequences need to be sufficiently idealized, such as what someone who did not violate any epistemic norms would have known.

Against Actual Consequentialism

We can consider a slightly modified case against the consideration of actual consequences:

Unknowable Medical Allergy: Smith gives Jones a medication that, according to all prior research, which was substantial, had a 100% cure rate and no known allergies. Unbeknownst to Smith or Jones, Jones has a very rare gene that reacts very poorly to something in that medication, a kind of allergic reaction that has never been documented in the history of the human race. It turns out that Jones had a fatal allergic reaction to the medication and died as a result.

Did Smith do something wrong? I think the answer is clearly no, Smith did not do something wrong. Smith did something that had excellent expected and foreseeable consequences. But, according to objective consequentialism, since this action was worse than refusing to treat Jones, or giving Jones a placebo, or giving Jones a medication with a 50% cure rate with known allergies as long as it turned out to not result in Jones’ death, then Smith did do something wrong. This seems like the incorrect conclusion to draw. In fact, it seems Smith did something commendable and the right thing to do, even though by freak accident it went poorly, so we should reject objective consequentialism.13 We can consider a real-world scenario, an unfortunately frequent one, of the wrongness of an extremely drunk driver that happens to get home safely.

The above example is an instance of what is called “moral luck”, which is a subject of much debate in normative ethics. It is for cases like the above that I think the kind of consequences that are morally relevant are the foreseeable consequences, those that are foreseen when the agent is acting rationally, i.e., meets all their epistemic norms (or something slightly more demanding than this, especially depending on the moral weight of the situation). The kinds of consequences that matter are an internal debate among consequentialists.

One nice feature of foreseeable consequentialism is that it eliminates the epistemic objection to consequentialism: we can’t know all the (actual) consequences of an action, so if consequentialism is true, then we can’t know whether an action is right or wrong and thus can’t have moral knowledge. On foreseeable consequentialism, however, it is trivially true that we can know all the morally relevant consequences of an action, as everything that is foreseeable is knowable, by definition. Thus, we can have moral knowledge.14 There is a more interesting and sophisticated version of this objection, called the cluelessness objection, that is beyond the scope of this blog post, though I’d like to revisit in the future.15

The Three Components of a Complete Moral Theory

Plausibly, a complete moral theory should specify three things: 1) a criterion of rightness/wrongness (which itself can be split into a theory of the good and a theory of the right that, when combined, relate rightness and goodness), 2) a decision-making procedure for how to consciously think about one’s moral choices, and 3) a theory of praise and blame (thanks to Ibrahim Dagher for emphasizing the separateness of (3)).

Perhaps I should call this tripartite combo a complete moral “package” or “framework” instead of a moral theory;16 I know many academic ethicists don’t really care about decision-making procedures and think moral theories are only about specifying a criterion of rightness, but I think this is misguided (ditto for virtue ethicists moral theories that only care about assessing character and not right action17). Obviously, it is a feature of a moral theory that it is action-guiding and gives practical suggestions for reasoning in one’s moral decisions. Now, consequentialists may even suggest virtue ethics for their decision-making procedure; that’s fine, and that’s not a ding on consequentialism.

Similarly, one may (and should) think that blameworthiness can come apart from wrongness, and praiseworthiness can come apart from rightness. I, for one, think praiseworthiness is better to correlate with moral goodness directly, not rightness, and blameworthiness with moral badness, not wrongness, though obviously there is an important connection between the two blameworthiness and wrongness. For example, if one is stuck in a situation where the only options are all vastly and completely negative and it was very easy for you to do the best option, it is hard to say this action would be praiseworthy. But then again, this action does not seem blameworthy either. Others have given better examples, but I will explore this in a future post. Suffice to say, I think one can be praiseworthy (to some degree) in doing something wrong,18 and one can be blameworthy (to some degree) without doing anything wrong.19 Further, there are degrees of blameworthiness and praiseworthiness, and that is not the case for moral rightness and wrongness (contra my professor).

The point of all this is to say: your normative ethic is not finished when you have specified the criterion of rightness, such as the one given by Maximizing Consequentialism above. On the other hand, to object to Maximizing Consequentialism on the basis that it does not simultaneously deliver a decision-making procedure and/or theory of praise and blame is misguided, as the specification given by MC is merely the criterion of rightness. Similarly, it is pointless to object to MC on the basis of assuming that the decision-making procedure is identical to the criterion of rightness, or any other assumed association between the criterion of rightness and either a decision-making procedure or theory of praise and blame, unless that consequentialist actually endorses them. The direct consequentialist thinks the decision-making procedure is identical to the criterion of rightness, while the indirect consequentialist does not (and I am an indirect consequentialist).

While I fully endorse the Maximizing Consequentialism criterion of rightness, and I roughly endorse a theory of praise/blame that scales proportionally with goodness/badness (though also depends on the deviance from rightness), I am much less clear on the correct decision-making procedure and do not pretend to know when that procedure should deviate from the criterion of rightness. I leave that to the ethicists to let me know when they’ve got that figured out.

The Holy Grail of Ethics

Great news! We have now solved normative ethics (as long as we ignore 2/3 of what I said in the previous section). We have specified which moral theory is correct…or at least we have carved out a sufficiently targeted subset of a specific family of moral theories as being the most plausible. I’d say that’s good enough progress for now. The correct moral theory is that of indirect Maximizing Foreseeable Consequentialism:

Maximizing Foreseeable Consequentialism (MFC): An action is right if and only if and because it has the morally best foreseeable consequences.

I’m glad I could relieve my readers of the burden of having to do all this difficult ethics stuff to determine the best moral theory (or at least the criterion of rightness). It was a lot of hard work to get this far, I’ll tell you. Now, the only thing we have left to do is to figure out which things are morally valuable and how we can best maximize them.20 Candy from a baby. I leave this as an exercise for the reader.

A Few Pedantic Notes for Completeness

Here are a few further clarifications about the relationship between various moral properties (right, wrong, permissible, impermissible, obligatory) and what happens in the case of ties. First, an action is wrong if and only if it isn’t right. That is, an action is wrong if and only if and because it does not have the morally best consequences, aka the negation of MC. Moral wrongness is a synonym for moral impermissibility, which is equivalent to saying it is obligatory not to do. Secondly, for a consequentialist, moral permissibility and moral rightness are co-extensive, so an action that is permissible will always be right, and an action that is right will always be permissible. The same is true for moral obligation and moral permissibility, for the most part. The only slight deviation from this is if two actions have a “tie at the top” (next paragraph). For more on these moral properties, see the definitions and “deontic square” in this section of a Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy article.

Consider the case of ties: if two (or more) incompatible actions, let’s call them A and B, are both as good as the other one, and they are both better than all other possible actions, then it is obligatory to do either A or B, but both A and B are individually permissible (and every other possible action is impermissible, aka obligatory to not do). This is true even though it is not individually obligatory to do A nor obligatory to do B, as you are free to pick between A or B. If B were individually obligatory, then A would be impermissible (as you cannot do both A & B, by stipulation of mutual exclusivity), but A is permissible, so B is not individually obligatory. This rule can be represented in deontic logic with the obligatory operator O(action) as O(A or B) but ~O(A) & ~O(B), where the tilde ~ means “not”, so ~O(A) means “it is not obligatory to A”. Outside of this tie scenario, an action is permissible (and right) if and only if it is obligatory, according to Maximizing Consequentialism.

Takeaways

Hopefully, this article helped you have a clearer picture of the nature of consequentialism as a moral theory and what differentiates it from other moral theories, which is that consequentialism explains the rightness or wrongness of actions solely based on their consequences. I gave a brief defense of maximizing consequentialism based on the Compelling Idea, clarified the value of “consequences” as the value of actions + effects, and defended the view that foreseeable consequences are the (most) morally relevant kind of consequences.

I should have been able to more robustly substantiate, if indirectly, why some of the objections mentioned previously fail against consequentialism. For example, we saw how ought implies can can fit into consequentialism, how we can value intentions intrinsically, how we can avoid doing moral calculus, how we can definitely know the relevant consequences of our actions, and why all objections of the form “action X is right/wrong, therefore consequentialism is false” fail. It is my dream that these poor objections can be quieted once and for all. It remains to be seen if that will happen, but you can help me achieve that dream by sharing this article if you found it helpful.

This is, in principle, done in a straightforward way. There is plenty of debate about the 1) success of consequentializing (especially regarding moral dilemmas and supererogatory actions) and 2) implications of consequentializing, but I will share Doug Portmore’s formula for consequentializing a non-consequentialist moral theory:

“For any act that the nonconsequentialist theory takes to be morally permissible, deny that its outcome is outranked by that of any other available act alternative. For any act that the nonconsequentialist theory takes to be morally impermissible, hold that its outcome is outranked by that of some available act alternative. And for any act that the nonconsequentialist theory takes to be morally obligatory, hold that its outcome outranks that of every other available act alternative.”

From Portmore, Douglas W. "Consequentializing." Philosophy Compass 4.2 (2009): 329-347, p. 330.

So, one simply needs to make value assignments to ensure the ranking of outcomes of possible actions is ordered in the way he specifies to guarantee a link between the consequentialist and non-consequentialist theory. He gives a “procedure” regarding agent-centered restrictions as well, which is simply making value assignments based directly on the non-consequentialist counterpart:

“Take the very feature that the nonconsequentialist says determines which act should be performed (in this case, whether the act involves either committing murder or allowing murder) and claim that this feature determines which outcome the agent should prefer” (ibid, p. 329).

The qualification of “sufficiently good” is general so as to be neutral between satisficing and maximizing consequentialism. Technically, this still leaves out scalar consequentialism, which only specifies when actions are better or worse but not right, but one can only attempt to be so general and to me it seems to be an obviously incomplete theory if it doesn’t give any criteria for when an action is right or wrong. Clearly, some actions are right and some actions are wrong, so without this result, the theory is incomplete.

I’ll make a much better version of this in the future but I already had this one from a few years ago that I made by hand. Please excuse the sloppiness.

This label comes from Mark Schroeder and has been widely adopted in the literature. Of course, not everyone thinks the Compelling Idea is so compelling, but they would be wrong.

There may be different ways of wording this premise, such as it being always permissible to “do the morally best thing”, or to “do the most good”, but these might make the argument be question-begging in virtue of how these phrases need to be interpreted. Another similar premise would be it being always permissible to “bring about the morally best outcome”. S. Andrew Schroeder’s rough summary is “bring about the best outcome” (in “Consequentializing and Its Consequences”), and Portmore summarizes it as “bring about the most good” (in “Consequentializing Moral Theories”). I adopted Portmore’s characterization in the syllogism.

At least, for the most plausible versions of consequentialism this is true. Accepting the existence of supererogatory actions is for weaklings. Thankfully, the Protestant Christian ethic knows no such thing (although see this PhD thesis turned into a book for arguments otherwise, but the “no supererogation” view is still the predominant understanding, to my knowledge). Just do the morally best thing. You should be perfect, after all (Matthew 5:48).

There is also the possibility of ties, which I clarify briefly later.

I think I can also give reasons for thinking there are no supererogatory actions that are independent of the MC criterion, such that (1) would automatically entail the MC criterion, but I won’t attempt that here. See, for example, Fritts, Megan, and Miller, Calum. "Must we be perfect? A case against supererogation." Inquiry 66.10 (2023): 1728-1757.

Note that here is where one can, if so desired, build “ought implies can” into one’s moral theory such that the option set exclusively consists of actions that one can perform, in whatever sense of the word your heart desires.

There is debate among total and average and probably 5 other kinds of utilitarians, but I’m ignoring that for now.

Nikil Mukerji proposes this act-consequence distinction as being meaningful and non-arbitrary:

A given event which can adequately be described both as part of an act and as part of its consequences should be regarded as a the latter (for the purpose of normative ethics) if it could, on some remotely plausible theory of the good, be called “good” or “bad.” (Mukerji 2016, p. 62)

This sounds fine, but the takeaway is the same given arbitrary partitioning: if x is remotely plausibly good, then x can be considered a consequence. Mukerji thinks his distinction excludes lying as being a consequence because nobody thinks lying has any intrinsic merit or demerit. I think this is obviously false. Actions of deception and dishonesty are bad, even if no one ever finds out, it doesn’t “hurt anyone”, etc. It may be right without being perfectly good, but it’s just that the further good consequences of lying make up for the bad of the lie. I think this is clearly the correct way to analyze even basic and permissible instances of lying.

Mukerji says that if lying could reasonably be considered good or bad on its own, then it makes Kantianism compatible with consequentialism, which he think should not be possible (I agree that isn’t possible). But on the framework I have proposed for distinguishing between moral theories, then merely the ability to say lying is intrinsically bad does not automatically tell me why any given action is right or wrong, and thus does not uniquely specify such a theory as consequentialist.

It seems ethicists are virtually unanimous in agreeing that the intrinsic value of actions is included in the consequentialist assessment of moral rightness and wrongness. I will be content to provide just one additional citation here:

“When consequentialists refer to the results or consequences of an action, they have in mind the entire upshot of the action, that is, its overall outcome. They are concerned with whether, and to what extent, the world is better or worse because the agent has elected a given course of conduct. Thus, consequentialists take into account whatever value, if any, the action has in itself, not merely the value of its subsequent effects.

This might sound odd, because when speaking of the ‘results’ or ‘consequences’ of an action, we frequently have in mind effects that are distinct from, subsequent to, and caused by the action. Consequentialists, however, don’t limit results to effects in a narrow or causal sense, because they are interested in the consequences not only of one’s acting in various positive ways, but also of one’s refraining from acting.”

From Shaw, William. "The Consequentialist Perspective." In Contemporary Debates in Moral Theory, Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell (2006): 5-20, p. 6.

Mukerji, Nikil. The Case Against Consequentialism Reconsidered. Springer, 2016, p. 116.

I recently thought of an indirect way to get out of this objection thanks to Chapter 1 of William MacAskill, Krister Bykvist, and Toby Ord’s book on Moral Uncertainty (which is available open access!) , as they try to differentiate first-order moral theories from higher order theories that take into account moral uncertainty. The reply would be to say that while Actual/Objective Consequentialism does not give the correct verdict all things considered, that becomes clear only in virtue of our moral uncertainty about the situation, and thus isn’t a problem for a first-order moral theory. The only way to get the “correct” implication is via a theory of moral uncertainty, not any first-order moral theory. However, I would reply that foreseeable consequentialism, which is a first-order moral theory, just does give you the correct implication, and thus this situation does count as a strike against Objective Consequentialism. Maybe there is a better way to formulate their (hypothetical) response, as I find this stuff a bit muddled at current moment, but I find this sufficient for now.

I suppose one complication is that it may be difficult for us to have knowledge of what is foreseeable by other agents, especially far removed from us in time or space. But at least it isn’t widely and totally unknowable or anything.

Like so many of my other writings, I started writing about this objection, and then I wrote too much and realized it was worth splitting into a separate blog post to get a fuller treatment. Every dang draft blog post I’ve set out to write has split into 3 separate blog posts. Anyway, the cluelessness objection comes from Lenman, James. "Consequentialism and Cluelessness." Philosophy & Public Affairs 29.4 (2000): 342-370.

A fourth possible component of a complete moral framework is an account of decision-making under moral uncertainty, which I’m currently taking a seminar on and will write more about, but this is definitely separate from a moral “theory” as traditionally understood.

Thankfully, there are exceptions to this general rule for virtue ethicists. See these discussions, for example,

Van Zyl, Liezl. "Virtue Ethics and Right Action." The Cambridge Companion to Virtue Ethics (2013): 172-196.

Hursthouse, Rosalind. On Virtue Ethics. OUP Oxford, 1999, p. 28.

It’s worth considering that virtue ethicists may have a point that other moral theories are incomplete if they do not also offer a theory of character evaluation in addition to action evaluation, which could include a distinct theory of praise/blame for agents (afaik it’s debated whether typical theories of praise/blame are for actions or for agents) as well as a distinct theory of goodness/badness for agents/character. However, this would not actually challenge, say, Maximizing Consequentialism as the right theory for action evaluation, only that consequentialists should also attempt to develop accounts of agent evaluation beyond that. That sounds fair. I am much more confident, however, that VEs should develop action evaluation accounts than MCs should develop agent evaluation accounts; I think there are some legitimate Christian motivations to avoid actively developing such a theory of agent evaluation, either because agent evaluation is automatically settled by Scripture and/or because a general theory of character evaluation is not a proper target of Christian contemplation. I leave this for future discussion.

Pummer gives an example where it is wrong to rescue fewer strangers rather than more strangers, which is praiseworthy (saving lives is really good and challenging and thus praiseworthy) but impermissible, in Pummer, Theron. "Impermissible yet Praiseworthy." Ethics 131.4 (2021): 697-726.

Capes discusses (but doesn’t endorse) an example where someone is hiding Jewish refugees and lies to the Nazis at the door, yet this person sincerely and deeply believes that lying is always wrong and is thus fully convinced she did something wrong. I am sympathetic to this kind of example, as it is blameworthy to have “demonstrated a willingness to do wrong”, which Zimmerman argues is a condition for blameworthiness, which makes sense to me. However, one wrinkle is that the story says she “believes every course of action available to her is objectively morally wrong.” This complicates things beyond the purpose of this footnote, so I’m going to move on.

Capes does endorse a “blameworthy without wrongdoing” scenario where a woman kills Bill out of (morally unjustified) hatred of Bill, while believing it is objectively wrong for her to do so, and yet, unbeknownst to her, killing Bill was the only thing that would have stopped Bill from torturing and killing her daughter. Capes says this killing would be justified from self-defense, whereas, I do not. In virtue of Bill’s intent being unforeseeable (assuming it was, as it was not specified that Bill was breaking and entering, for example), then I don’t think killing Bill would be justified. Objective consequentialists, on the other hand, would agree with Capes (depending on what they would say about moral value of motivations).

Both these examples are from Capes, Justin A. "Blameworthiness without wrongdoing." Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 93.3 (2012): 417-437.

One may also be able to be blameless in wrongdoing, as proposed in Tännsjö, Torbjörn. "Blameless wrongdoing." Ethics 106.1 (1995): 120-127.

I probably should, you know, say something about the plausibility of and arguments for/against other moral theories, too, at some point. But hey this is only my 3rd substack, give me some time!

Good to see another post! There’s a lot to dig into here.

Like this quote:

“Clearly, it is wrong to intentionally do something worse than your best.”

This is interesting, for I do not think this is “clearly” true.

Suppose I come upon $100. Feeling generous, I decide to give you $25. I keep the rest for myself.

Now, I did not do the *best* I could do in that situation. The maximal degree of generosity would have been giving you all $100. But did I do something impermissible by only giving you $25? That doesn’t seem like the right interpretation.

I regret that "criterion of rightness" and "decision procedure" are the lingo we're stuck with. An scheme based just on the notions of axiology and decision theory seems more unifiying, and can help dissolve disagreements between consequentialists. With a list of goods (that usually won't include acts themselves or consequentialized objects), and given a background decision theory that involves any broad of optimality, we're talking now about the broad consequentialist family. Debates between global and act consequentialist in this picture turn out to be decision theoretic, and track discussions in that literature that most writing about this distinction have ignored (resolute Choice, dynamic consistency, cubitt axioms, FDT vs EDT). Blameworthy and wrong can be collapsed into "person that failed to follow- or act chosen from something other than- the specified decision theory". Very puzzled by your characterization of the DP vs CoR debate, it seems that if we adopt that lingo and are gonna be indirect consequentialists we'd be comitted to claims such as "you should follow this decision procedure, but it's not the right thing to do". To the question "why should I follow this decision procedure?" you cannot give the straightforward answer that it's the right thing to do or refer to the criterion of rightness if the criterion was already cashed out in non-actual consequentialism terms (and even in this case if you keep asking why am not sure you'll get an answer that doesn't collapse CoR and DP, contradicting the first step).